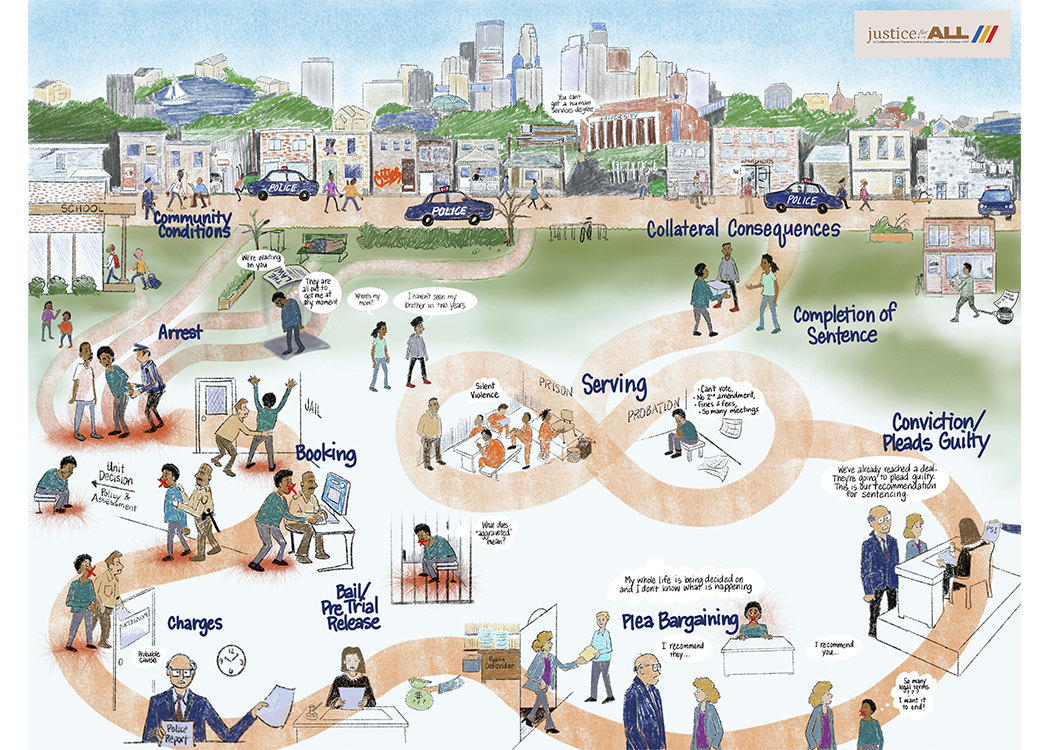

Click on the image to view and download a PDF version.

“Complex” only begins to describe the criminal justice system in Greater MSP. It involves three separate branches of government, each with multiple layers of jurisdiction. This complexity makes it possible to conceal inequities from those without direct, lived experience within the system, and makes it possible to maintain an unjust status quo.

Surfacing the root causes of inequities in our criminal justice system requires a deep understanding of that system, through the eyes of those most affected by its inequities. With that in mind, Justice for All worked with its Community Advisory Committee and used findings from its community-driven research process to create an illustration of the criminal justice system in Greater MSP.

This illustration is intended to bring light to a system that’s challenging to understand, even for those who live and work within it. It also shows what’s possible – by understanding the system, we can collectively begin to change it.

We can see the Community Conditions – the sheer number of onramps into the criminal justice system, and how arrests affect families and communities.

We can then see how interactions with police and the court system are weighted against the individual – a disempowering experience that often leaves few options other than plea bargaining. Because of overwhelmed and under resourced public defenders, people in the court system feel pressured to make decisions without fully understanding the implications of those decisions.

We can also see that once people enter the corrections system, they often navigate a long cycle of prison and probation, with little to no support, or opportunities. Upon exiting that cycle, people often return to the same Community Conditions, and the onramps that introduced them to the criminal justice system in the first place, and again with no support.

We’re grateful to Kriss Wittman who worked with Justice for All to create this illustration. This work also included deep listening to the Community Advisory Team, who shared the following experiences to inform the illustration.

Community Conditions

The Illustration begins with Community Conditions, showing an overpoliced community. Stemming out of the Community Conditions, we can see the numerous onramps into the criminal justice system. We heard that first encounters with the criminal justice system were occurring as early as thirteen years old.

We also heard a pervasive sense of fear. This can be seen in the onramp that features an individual saying, “They are all out to get me at any moment”. The Law is there too, saying, “We’re waiting on you.” In our listening sessions and interviews, we continually heard that The Law constantly targeting and hanging over Black folks, which emerged as a predominant understanding from our community-driven research process.

Arrest

For many, an arrest is the entry point into the system. In the illustration, an individual is arrested by a police officer, taken from their community and family and placed in Jail. Throughout our listening sessions, many participants described seeing adults in their lives arrested by police at a very young age, and they shared the pain and harm of having their families broken up. This shows that experiences in the justice system do not only affect the arrested individual – they affect families and communities too.

Booking

The justice-impacted individual is then taken to Jail, where they are strip searched, processed, and booked by the Sherriff’s department. The red “X” over their mouth illustrates the individual often not being allowed to advocate for themselves once they enter the system – it’s the police’s word against theirs, and the system gives significant weight to the voices of the police. Even beyond the arrest stage, an individual is often discouraged from speaking for themselves, instead being asked to allow legal professionals to speak “for” them.

Charges

Here, the Prosecutor is shown reading over the Police Report, which is the document outlining probable cause, or the police’s justification for arresting the individual. It’s usually a thin report. The Police Report drives much of the work of the Prosecutor. The Prosecutor is depicted as larger than the other system actors (the public defender, the Judge, etc.) in the illustration to show the relative amount of power they possess in the courtroom from this point all the way through to conviction. We heard again and again that individuals need to worry about the Prosecutor, since they have the power to determine the fate of that individual within the justice system.

Bail/Pre-Trial Release

The Judge is shown determining bail. Although the Prosecutor makes the recommendation for bail, we heard that the Judge often follows that recommendation without reviewing the case themselves. The bag of money to the right represents the cash bail system. Above, the individual is shown in a jail cell wondering what “aggravated” means. This feeling of confusion is shared by many individuals going through the system, and especially at this stage through conviction – we often heard that individuals are asked to make decisions without fully understanding the implications of those decisions.

Plea Bargaining

The Public Defender’s desk is shown with papers and case files stacked high. We heard again and again that the Public Defender seems to be working with the Prosecutor and isn’t truly on the side of the individual going through the justice system. One individual said that, “The government is prosecuting me, and the government is defending me”.

On the flip side, we heard that the Public Defender is overworked. That, loosely, for every 50 cases the Prosecutor has, the public defender has 150 cases. In the picture, the Public Defender is depicted picking up the case file as they enter the courtroom, illustrating just how little time they have to handle the case which is about to determine a person’s life.

Next, the Prosecutor is shown saying, “I recommend they…” followed by the Public Defender turning around to the individual they are representing saying “I recommend you…” indicating that they are working together and the Prosecutor is driving the negotiation, which is really does not feel like a negotiation.

Meanwhile, the justice-impacted individual doesn’t have much knowledge of what is actually happening. They just want this process to end, to go see their kids or be with family, to leave jail where the conditions are viewed as worse than the conditions of prison. They just want an end.

Conviction/Pleads Guilty

Here, the Prosecutor and Public Defender are shown presenting the plea deal to the Judge. Approximately, 95% of cases are settled with a Plea Deal and never go to trial. The justice-impacted individual is portrayed as saying, “So many legal terms? I just want it to end!”.

Confused and wanting an end, many agree to plead guilty without knowing the full implications of that decision – they just want to get home to their families or simple to have an end to the confusing ordeal. At this point, the Judge is handed the PSI (Pre-Sentencing Investigation), a document that outlines background information and life context about the justice-impacted individual to help Judges determine sentencing. Typically, this document arrives too late, as the Prosecutor and Public Defender have already reached a deal for the individual to plead guilty.

Serving

Shown here is the infinity loop of Prison and Probation. Many shared that these two parts of the process felt no different: the extreme lengths and limitations of Probation felt comparable to being incarcerated – one cannot vote, 2nd amendment rights are revoked, there are meetings, fines and fees (including paying fees to work, if sentencing includes being in a workhouse).

In the illustration of Prison, the words “Silent Violence” are shown. “Silent Violence” is the harm done to those incarcerated that no one sees – the mental toll, the isolation, the impact on the families of the justice-impacted individuals.

Above, there are children asking the questions of, “Where’s my mom?” and “I haven’t seen my brother in two years”, to illustrate that families and communities also feel the impact of an individual serving time.

Completion of Sentence & Collateral Consequences

When sentences are completed, the justice-impacted individual is dropped back off right where they were picked up, in the original Community Conditions that led to their involvement in the criminal justice system. To the right, the individual is shown searching for work with a ball and chain tied to their ankle, illustrating how difficult it is to find an occupation, housing, and a degree with a criminal record. The justice-impacted individual is now expected to reenter and contribute to society.